This is a follow up to The Evolution of Western Chess. You might want to read that article first to hear about the common ancestor of both branches: Chaturanga.

Firstly here is the family tree that we explored the left hand side of last time:

Xiang Qi is often referred to as Chinese Chess in the West and has a few immediately marked differences from Chaturanga. Lets look at a set that I managed to pick up in Chinatown in New York:

Xiang Qi

This already looks strange to people used to Western Chess, but most of the pieces have direct equivalents. The front 5 pieces on each side are the soldiers, they go one space forwards until they get over the river in the middle of the board, at which point they can go sideways as well. All of the moves are played on the intersections of lines rather than the squares, which makes the board the equivalent of a 9x10 rectangle. The backrow goes Rook, Knight, Elephant, Adviser, General, Adviser, Elephant, Knight, Rook. Rooks are the only piece that move exactly as you would expect.

Knights go one space horizontally then one space diagonally carrying on in the same direction. This makes them end up in the usual place, but without the ability to jump. Elephants are more similar to the elephants of Shatranj (and possibly Chaturanga, we don't know). They move 2 spaces diagonally, but are purely defensive because they are unable to cross the river. This means they only have 7 spaces that they can actually reach.

The palace is the 3x3 area around the General. Both the General and the Advisers are stuck inside, and the Advisers can only move diagonally (just like the Chaturanga Councillor which evolved into the Queen on the Western branch; very divergent evolution). This doesn't leave many pieces that can actually launch an attack.

Luckily that doesn't matter too much because the General is so trapped in the palace that checkmate doesn't require many pieces. The Generals are never allowed to directly face each other with no pieces in between. It is like they have a hypothetical vertical move against one another.

But the most interesting piece in the game is the Cannon (middle rank). It moves like a rook, but it takes by hopping over a piece. This creates really interesting gameplay where removing your own pieces from in front of your king can remove a check. It also becomes possible to get triple, or even quadruple checks, which is a nice, little puzzle to work out.

I'm only going to briefly mention Janggi which is the Korean descendant of Xiang Qi. The main difference is that the river is gone. This means that the Soldiers don't have to be promoted to be able to move sideways and the Elephants can be used offensively. However I can't seem to find much on the history of the game or even which century it began in.

However Shogi (Japanese Chess) has a rich history starting in the 12th century and has a huge player base even to this day. It may have lost some ground to Go in terms of most played game in Japan, but it is still very well known.

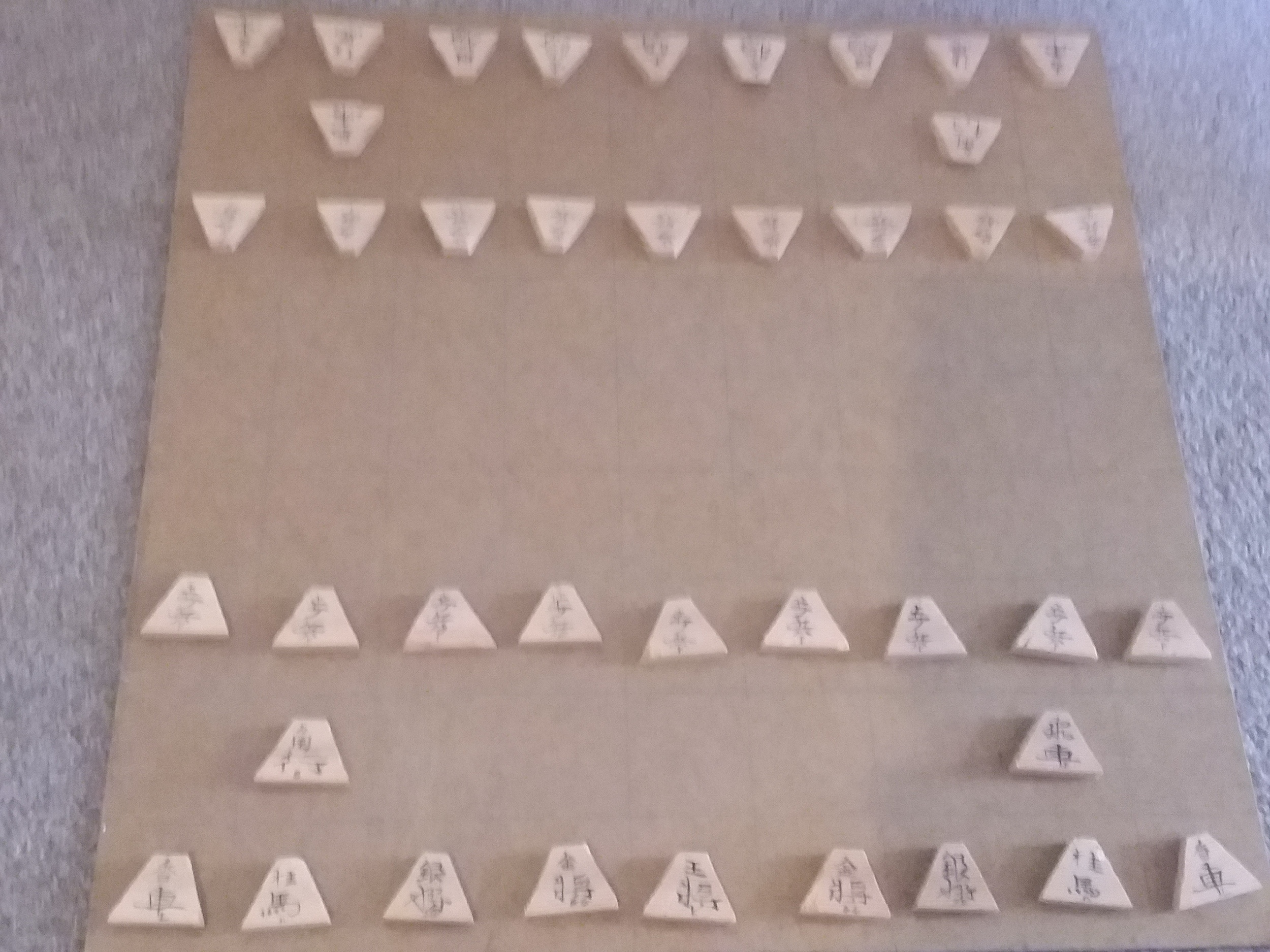

Here's a set I made when I was 16:

Shogi

Up in front we have the pawns which just move forwards. In the next rank we have the most powerful pieces in the game, one bishop and one rook. Back rank we have Lance, Knight, Silver General, Gold General and a King in the centre before having the same on the other side. Lances and Knights are like the only going forwards versions of their Western chess countrerparts and the SGs and GGs move like kings with a couple of options missing. The specifics are quite long and I'll skip them. Observe that you can see the layout slowly evolve through Chaturanga->Xiang Qi->Shogi.

Close up of front sides. English initials underneath.

What makes Shogi interesting is that if you take a piece, you may use your turn to replace it on the board but on your own side (similar to Partner Chess). This wouldn't work in a game where people played with different colours, but in Shogi the orientation of the piece determines its allegiance. This creates a completely chaotic game with lots of small range conflicts going on all over the 9x9 board.

Almost every piece can promote by flipping to show its reverse by landing anywhere within the last 3 ranks of the board (i.e. within enemy territory). Most pieces promote to the equivalent of Golden Generals but there are more exotic Dragon Horses and Dragon Kings out there. Here are some of the reverses:

Reverse side with the promotions.

Around the playing of the game there is a lot of very Japanese tradition (much like Go with its specific way of holding the stones) and even the order in which the pieces are placed on the board at the start of the game is controlled. This and its fairly untranslated opening theory make it quite hard to make progress into as a Westerner, but I think that the base game is my favourite in the whole tree.